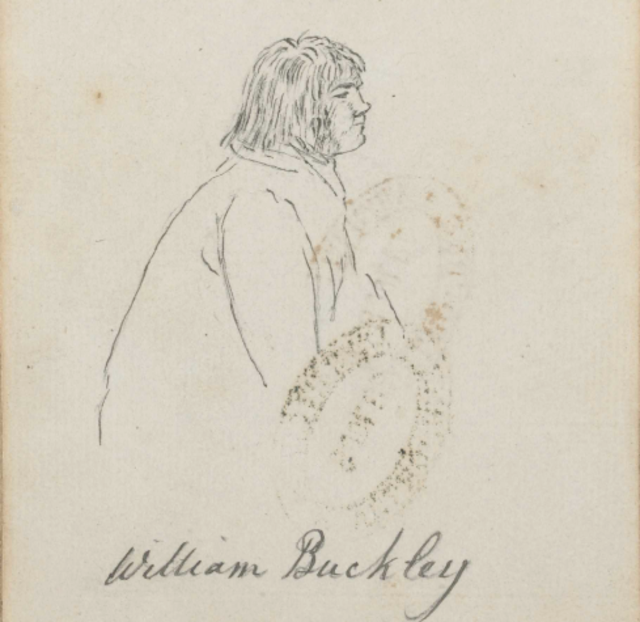

Australian Slang: Who Was Buckley and Why Didn’t He Stand a Chance?

“You’ve got two chances mate, Buckley’s and none”

William Buckley had a history of running away. Apprenticed to a bricklayer in England, Buckley’s first escape effort saw him enlist in the army and eventually deployed to a campaign in Holland. On returning to England in 1799, Buckley fell into misfortune.

William Buckley had a history of running away. Apprenticed to a bricklayer in England, Buckley’s first escape effort saw him enlist in the army and eventually deployed to a campaign in Holland. On returning to England in 1799, Buckley fell into misfortune.

“At the barrack yard, I was one day accosted by a woman who requested me to carry a piece of cloth in a parcel to a soldier’s wife in the garrison to be made up. I knew nothing of the person. She was a stranger to me; but I took the parcel to do as she wished and was almost immediately arrested for theft.” — William Buckley, as recounted by George Langhorne, transcribed in 1836 and published in The Age, Saturday 29 July 1911.

With Buckley’s tale of the woman with a cloth discounted, he found himself sentenced to transportation. The Calcutta arrived in Port Phillip in 1893 under the command of Lieutenant Colonel David Collins. Collins’ brief was to establish a penal settlement, but his party soon discovered the soil sandy and incompatible with English crops. Collins soon decided to abandon the area, aiming his sights on Van Diemen’s Land instead.

Escape!

With no interest in being whisked off to Van Diemen’s Land, Buckley and some mates hatched an escape plan. Previously other convicts had absconded, and while none had been successful, this did not deter Buckley. He was going to grab hold of the slim chance of liberty or die trying.

On Christmas Eve, as the soldiers enjoyed a little too much to drink, the group stole a kettle, gun, boots, and medical supplies. Several days later, under cover of darkness, they made their move.

One of the convicts was shot during the escape, but five men, including Buckley, melted into the Australian bush. Deciding they had bitten off more than they could chew, two of the convicts turned around and handed themselves back in. Buckley and two other companions continued trekking through the bush until they reached the opposite side of the bay.

“I and my two companions traveled on until we fell in with the Yarra, and tired and weary with our journey, sat down and ate the last of our provisions.

This was near the place of the present settlement. We again started on our wandering. I thought that by keeping in a northerly direction we should soon reach Sydney, at Port Jackson; but my companions differed with me, and we parted company, I resolving to travel alone.” — William Buckley, as recounted by George Langhorne, transcribed in 1836 and published in The Age, Saturday 29 July 1911.

Survival rating: Next to impossible

The chance of Buckley making it this far had been slim to none, yet still he persevered. Now with Buckley’s departure from his companions, his survival rating was next to impossible. Fortunately for Buckley, there was no one to tell him these odds, and so he carried on, foraging for food as he walked.

This is where Buckley’s story should have ended. Just one more escaped convict perishing in the Australian bush in an attempt at liberty.

Wild White Man

In July 1835, a “wild white man” walked out of the bush and handed himself in to the party under the command of John Wedge at Indentured Head. Communication was at first difficult. The man seemed to have forgotten his native tongue. Slowly words came back to him, and the tattooed initials WB on his arm confirmed his identity.

William Buckley.

Regaining his voice, Buckley recounted his thirty-two years living amongst a tribe of indigenous Australians.

“My not being able to talk with them, they did not seem to think at all surprising — my having been made white after death, in their opinion, having made me foolish; however, they took considerable pains to teach me their language, and expressed great delight when I got hold of a sentence, or even a word, so as to pronounce it somewhat correctly; they then would chuckle and laugh, and give me great praise.”— William Buckley, as recounted by George Langhorne, transcribed in 1836 and published in The Age, Saturday 29 July 1911.

“I was able to express myself in the aboriginal tongue pretty freely, and in a very short time after, I could converse freely with them. But when I had attained their language I found I was fast losing my own. My situation, however, was now less irksome, and I was able to converse with them about their tribes and manners and customs.”— William Buckley, as recounted by George Langhorne, transcribed in 1836 and published in The Age, Saturday 29 July 1911.

Van Diemen’s Land awaits

Despite Buckley’s reluctance to talk about his time in the bush, Wedge saw an opportunity. Buckley’s knowledge of the indigenous Australian culture and their language made him valuable. Wedge secured a pardon for Buckley and employment as an interpreter.

His position as interpreter confused Buckley. He no longer knew where his loyalties were. To his white kinsmen? Or to the tribe who adopted him and kept him safe for thirty-two years? Furthermore, he didn’t know who he could trust. Perhaps everyone was playing on his loyalties?

In 1937, Buckley once again ran away … to Hobart, the heart of Van Dieman’s Land. Having come full circle and arrived at a place he had once been desperate to run away from, Buckley held a relatively normal life until he died in 1856.

Buckley’s chance

Buckley’s tale of survival against all the odds has seen him ingrained in Australian folklore and slang. To be told you have “Buckley’s chance” ironically means you have no chance at all — despite the fact that Buckley survived with next to impossible odds.

Sources

Australian Dictionary of Biography

Culture Victoria

Trove | National Library of Australia

The Age Newspaper (Melbourne, Vic. : 1854–1954)